Noć je emulzija za snimanje svjetla. Nitko ne zna što snima priroda.

Many narrative filmmakers have recognized the expressive power of landscape as a time-based element. But most would acknowledge that two markedly different avant-gardists have taken the medium further than anyone else: James Benning, a Wavelengths regular, is one; Peter Hutton is the other. While Benning’s work tends to systematically organize the living environment (13 Lakes, Ten Skies), Hutton’s films are about the ineluctable drift of things. His films get out on a river (Time And Tide), or set up along the side of a hill (Skagafjordur), and patiently observe as nature unfolds in its own sweet time.

Hutton, whose 47-minute “Three Landscapes” debuts this year, is a longtime filmmaking professor at Bard College in New York, and he’s drawn extensive inspiration over the years from both the Hudson River and the school of painters associated with that region, Thomas Cole in particular. Accordingly, Hutton’s work has explored land and water as phenomena of light, capturing their luminosity in misty, diffuse circumstances as well as in piercing direct sunstream. His films rely on the character of 16mm celluloid; most are black and white, all are silent. Hutton employs the diffusion of swirling film grain to replicate the atmospheric specificity of environmental light. He’s filmed throughout the world, from China to Iceland and beyond, emphasizing the absolute qualities of light in different places. Hutton’s latest returns to the Hudson while also examining northeastern Ethiopia and his troubled hometown of Detroit. - Michael Sicinski

By Max Goldberg

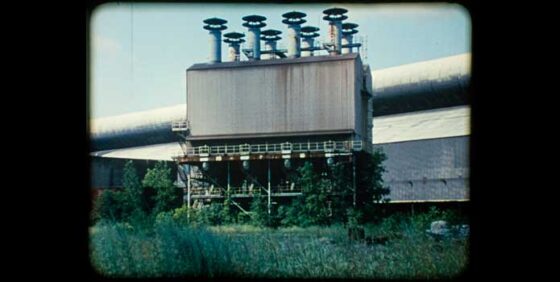

One of several triptychs showing in this year’s Wavelengths program, Peter Hutton’s Three Landscapes zeroes in on the industrial terrain ringing Detroit (where he grew up), the bucolic pastures of the Hudson River Valley (where he now lives), and Ethiopian salt flats (where he travelled under Robert Gardner’s sponsorship). The most obvious link between the three is labour, but the film functions less as a thesis statement than a poetic meditation, a haiku-like attempt to distill the landscape using a few sparing, echoing graphic forms. The Detroit sequence is the most immediately arresting, its subdued colour palette and precise graphic calculations of grass, clouds, sky, smoke, and industrial architecture leading to a dramatic chain of images of two men inching across a high ladder—a vision of meditative calm in struggle. Workers and clouds are combined to more expressly lyrical effect in a superimposition punctuating the Hudson River Valley sequence, a marvelous bit of photochemical guesswork (albeit one now rendered in DCP projection). If the Ethiopia sequence seems comparatively uncertain about itself, its final long take of a line of camels stilled by distance and heat closes the film with an eloquent appeal to the necessity of limits. After the screening Hutton remarked that he takes special pleasure in those landscapes in which you see clouds moving faster than the workers, a point of view that goes a long way towards restoring the link between the documentary and spiritual connotations of this word “observe.”- cinema-scope.com/cinema-scope-online/tiff-2013-three-landscapes-peter-hutton-us-wavelengths/

Peter Hutton, 3 Landscapes, 2011

Courtesy: the artist

Courtesy: the artist

Lived Experience

Luke Fowler and Peter Hutton have their own particular lines of research that have at times led to synergies, but which above all share precise affinities, starting with the anthropological and historical intent of their films—which explore geographical places and human movements with a poetic impulse—to achieve the attitude of the true explorer, the artist who crosses localities and boldly roams in search of stories. As readers, we can let ourselves be wafted along on their conversation, in pursuit of carovans of camels crossing the horizon, observing salt mines and peasants at work...

| Luke Fowler: I understand you are filming your next project in three places: Detroit, Michigan; Mekelle, Ethiopia; and the Hudson River Valley in New York State. What drew you to these locations? Peter Hutton: The new film is tentatively titled Three Landscapes. The first section was shot near Detroit, where I grew up. I worked as a merchant seaman on the Great Lakes during the 1960s (I continued to work on ships throughout the early 1970s) and my union hall was in River Rouge, a heavily industrial area. I spent a few weeks there again three years ago, documenting a steel plant called Zug Island, which is still functioning. It was a security nightmare to film. Another steel mill, an abandoned one, became a source of some additional images. I traveled along West Jefferson Avenue nearby, and recorded whatever appealed to me. It culminated in a study of two men walking up the suspension cable of the Ambassador Bridge, which connects Detroit with Windsor, Canada. All the material feels like a dream, which is appropriate, since so much of the landscape surrounding Detroit is dead. The Hudson River Valley is my home. In the summertime I’m always amazed at how beautiful the landscape is. The dry green meadows, where the hay bales cast long shadows at that magical hour of the day. The clouds rolling above the Catskill mountains—huge thunderheads—are stunning, evoking dreams. I remember reading an account of Henry Hudson’s voyage up the Hudson River, and how fragrant the land was to the sailors on board his ship; they could smell the abundant fruit trees. From the dispiriting climates of Western Europe they thought they had arrived in paradise. The final landscape I will shoot is Ethiopia. In 1968 the filmmaker Robert Gardner went to the Dallol Depression and made a very short film about the Afar camel herders who harvest salt there. It’s the lowest spot in Africa, which is essentially a vast salt deposit. It’s also one of the hottest places on Earth. In 2010 we showed his film as part of a retrospective of his work at Bard College, where I have been teaching since 1984. Gardner asked me then if I would be interested in going to Dallol to expand on what he did in 1968. His film is quite beautiful but also very short. I agreed. So, last year I went to Ethiopia with my wife and a cinematographer friend, Mott Hupfel. We planned to camp out in the area for five days. The day before we were to depart to Mekelle from Addis Ababa, a group of rebels from Eritrea came across the border, murdered six European tourists, and kidnapped two German citizens. As a result, the Ethiopian government shut down foreign travel to that region. Now it’s a year later and I’m preparing to go back and try again. One of the most haunting images from Gardner’s footage is a distant shot of a camel caravan crossing the horizon. Because of the intense heat waves, the landscape seems to be melting. One is not sure if it is real or a hallucination. I am haunted by that image—it is like something you might see right before death, an ancient memory about traveling. This, I hope, will be the focus of my film. What exactly this has to do with my material of Detroit, or for that matter the Hudson River Valley, I’m not entirely sure. There is some irony, however, in the fact that I shot a huge pile of salt in Detroit three years ago. There is a vast salt mine under that area of the city. I actually tried to go into the mine and shoot in the 1960s but was denied permission at that time. What a metaphor for Detroit!  Luke Fowler, A Grammar of Moving, 2010 Luke Fowler, A Grammar of Moving, 2010Courtesy: the artist; The Modern Institute/Toby Webster Ltd, Glasgow; Galerie Gisela Capitain, Cologne LF: You spend so much time studying the movement of people, work, and the environment. Do you see your work as having an intrinsic anthropological and historical value? I do see my work in that way. PH: Well, for instance, the slow processes of humans engaged in agriculture in the Hudson River Valley are quite remarkable to watch, and I believe that it is necessary to record that agrarian sense of time. All the figures working: farmers plowing the rich black soil and cutting the hay, planting and harvesting crops. They are young and old, from different parts of the world, all moving very slowly across the land. Often I’ll watch a group crouched over pulling weeds for hours in the blazing sun, just inching along. Time almost stops. It’s an activity that seems more suitable to painting; often the clouds are moving faster than the workers. Is this cinematic? The slowness seems to me a revelation of sorts. These people are undoubtedly going to heaven in my world; they belong there after bending down all day in the summer heat. There are also, of course, machines, like the tractors that rumble along cutting hay; they look as though they are swimming through the long grass. The funny hay baling machines look like large mechanical bugs shitting out very large, round turds that roll along the ground with steam rising, which is actually hay dust. How biomorphic and allegorical it looks to me. LF: Your films often remind me of Raymond Williams’s book The Country and the City, where he talks about the false dichotomy between those two geographies. For example how people from the city view the country with romantic whimsy, though in reality the country is a place of work that interconnects with the city in vital lines of communication, industry, and politics. Do you remember the quote I used in our film The Poor Stockinger, where Williams talks about the idea in painting of “the prospect”: The signs of people working in the landscape are often seen as obtrusive of spoiling the landscape... There is a sense that when you’re looking at a picture, you want to control and compose the elements, you want in a sense to put a frame around them, as people still do in photography. Too much movement, too much life is going to contradict what you are looking for. I think the idea in the 18th century of “the prospect,” where you found yourself a commanding point of view and looked over some tract of the country, which was increasingly often like landscape pictures that you’d seen... that [practice] does involve separation from the country as a place of life and work. How do these ideas relate to your work? PH: I have traditionally bounced back and forth between city and country projects and definitely feel they are connected in many ways. It’s very ironic in today’s crumbling urban spaces—Detroit, for example—where the city is being encroached upon by the country by way of “urban gardens” and “country” markets, the “green belts” and the strong importance of “open spaces.” I always thought the experience of being at sea gave me a greater awareness of urban spaces in that it made me acutely aware of nature’s influence on the city environment. I remember once reading an account by the painter Albert Pinkham Ryder. There was a parade in Greenwich Village and he was sitting on the curb watching clouds overhead. I’ve always loved the seascapes he painted of New Bedford, Massachusetts. I was a painter when I was young, and painting remains a primary influence on my filmmaking. There is a lot of self-referencing in many of your recent films, very much like a diary. Why is that? LF: It’s pure narcissism! Ha, just kidding. I think there are many reasons. One is a reaction against the spurious notion of objectivity in nonfiction film—that somehow these films are impartial or objective and do not encode the beliefs and opinions of the makers. I remember watching documentaries on the BBC when I was growing up and the end credits would list no director, only a producer. Which confused me, as quite often there would be the most overpowering “voice of God” narrator over the top of the imagery. Sometimes it can be simply a pragmatic reason, you know, to bring a figure into the frame. I have also filmed people I’ve worked with or lived with: Lee Patterson, Eric La Casa, Toshiya Tsunoda, my mother. I believe you and George are on that list now too.  Peter Hutton, Boston Fire, 1979 Peter Hutton, Boston Fire, 1979Courtesy: the artist PH: Can you talk about your desire to create alternative histories regarding characters from social history: R. D. Laing, Raymond Williams, et cetera? What feeds your urge, as an artist, to revisit history? LF: Of course we both know that history is constructed, researched, edited, and structured (often around narratives). I am inclined to reject the simple motives that narrative or documentary film often provides us with. Instead I adopt, as you do, an open, observational tendency, with a preference toward the polyvalent. You mention Raymond Williams, who I have not ever devoted a film to, and perhaps I should. I find his work important in that it attempted to expand into sociology and literature in the late 1950s the notion of a “common culture” and the importance of “lived experience.” R. D. Laing, in whom we share a mutual interest, also put emphasis on the experiences of the people he worked for and broke bread with. He wanted to understand the thoughts and utterances of those who conventional psychiatry had cast off as unintelligible, illogical, mad. His manner was personal as opposed to diagnostic; he avoided categorizing and schematizing human experience. He was prescient in stating that madness was often a political issue with strong social, environmental, and interpersonal dimensions. In short, I believe in what E. P. Thompson hoped to achieve in those North Yorkshire WEA night classes: the need to create more revolutionaries. He wanted to reconnect working people with a history of dissent and struggle, to show them they had the agency to shape their own history. If history is a construct, it’s a construct that is owned by the victors. I hope to return history to the voices that in those struggles have become marginalized. We have in the past discussed our mutual admiration for the work of your peers James Benning and Nathaniel Dorsky, and yet you seem equally close, personally and professionally, to the anthropological filmmaking of Robert Gardner. Do you think your work somehow bridges the different values of these two distinct worlds? Or perhaps they are not as distinct as I perceive them. PH: When I started making films in the 1960s, I thought all I really needed to do was live an interesting life and continue to travel, and things would take care of themselves. I’ve always admired artists who lived in the world. Gardner did just that. Ben Rivers, whom I greatly admire, does that too. I think it’s got a lot to do with the idea that “truth is stranger than fiction.” I’ve always felt that there is an amazing film going on all day, every day, right in front of us. When I was young in the 1950s my father often took me and my brother to see travelogues screened at the Detroit Art Institute. These were wonderful amateur movies made by a wide variety of people who loved traveling. They ranged from trips to Yellowstone National Park in the U.S. to more exotic fare, films made in Europe and Asia. Some were quite cleverly shot on Bolex; others were more direct, with heavy-handed use of voice-over. My father loved these films. He had made his own photographic records of his travels as a merchant seaman when he was young. His photo album greatly affected me as a child. I remember going to see Mondo Cane with him when it played in a theater in Detroit. In the early 1960s he created a film society with a friend, and they screened films by Jacques Tati, among others. He once got a letter from Tati thanking him for showing Mr. Hulot’s Holiday so often! These influences seeped into my rather naive brain. I always wanted to be an artist but never imagined I would end up making movies. Then in the mid-1960s I picked up an 8-millimeter camera and began documenting performances that I had created as a sculpture student at the San Francisco Art Institute. The films abstracted the performance and were far more interesting for me. It was at this time that I began considering film a suitable medium for my creative yearnings. I sometimes think that I’ll someday end up painting again. The demise of film is helping hasten that. Why do we make films, anyway? We both share a love of film and creating records of our lives directly on film. LF: When I am making a film I am often motivated by the idea that I feel comfortable inhabiting the world of my subject for a long period of time. During this period I throw out, usually quite quickly, any idea of a thesis, script, or preconceived notion in order to drift between intuition, experience, and research. Its not that I am afraid of committing to an idea or making a statement; I am just resistant to a positivist procedure that forecloses on experience, on being able to react to the shifting realizations and circumstances that inevitably come about during the process of making. I learn, in the broadest terms, through the making. In return, I feel I have a duty to offer something back to the public that honestly reflects my process and method. Although I realize that (as with your films, which are all silent) some of what I am trying to do may be lost on people who are used to channel surfing, or constantly scouring the Internet. |

moussemagazine.it/articolo.mm?id=945

Figures, landscapes & time by Peter Hutton

The collection of seven films presented in the exhibition at La Loge represents over three decades of work by American independent filmmaker Peter Hutton. The exhibition features a number of early works including Boston Fire (1979) and Landscape (for Manon) (1986-87) and traces the artist's oeuvre through to the present. The main highlight of the exhibition is the debut of Hutton's latest films, Three Landscapes (2013) and At Sea (2004-2007) in the form of an installation.

Throughout his career, Hutton has used film to capture subtle moments in time in a way that reflects a powerful, contemplative method of viewing the world. In each of his films, he positions himself as a witness; he uses the camera to make a record of chosen landscapes filmed from a distance. Therefore, a tangible line can be felt in his films, separating the filmmaker from the reality that he is filming. His entire body of work results from patient observation as opposed to constructing a manipulated or staged reality.

Before becoming a filmmaker, Hutton spent a decade living and working on large merchant ships. He paid his way through art school with the money he earned at sea. The experience of witnessing the world by boat undeniably forged the artist’s sense of looking as a means of experiencing time and reality with a more intense focus on the subtleties of vision. The artist explains that, “there’s a kind of culture of survival when you’re out at sea, where you have to develop a kind of visual acuity to know where you are going and what’s happening.” Another defining aspect of Hutton’s work is his early artistic career as a painter. Though the artist abandoned painting for film in the mid-1970s, his films convey a visual connection to the methodologies of painting. As Hutton describes, film is “about painting with the language of cinema.”

Born in Detroit and a current resident of the Hudson River Valley, Hutton’s personal connection to specific places is evident in his work. His long appreciation for the beauty of the Hudson River Valley is expressed in a number of his films including Landscape (for Manon), Study for a River and Three Landscapes. His cinematic treatment of this area has been linked to the mid-19th century painting of the Hudson River School, an American art movement known for romantic depictions of the natural landscape surrounding the Hudson River. Often using his daily life as inspiration, Hutton believes in the adage that truth is stranger than fiction.

Hutton’s oeuvre consists of a rich collection of over twenty films that portray a sense of meditative timelessness. The seamless movement of man and nature appear as continuous forces untouched by time. - www.la-loge.be/project/figures-landscapes-time

Throughout his career, Hutton has used film to capture subtle moments in time in a way that reflects a powerful, contemplative method of viewing the world. In each of his films, he positions himself as a witness; he uses the camera to make a record of chosen landscapes filmed from a distance. Therefore, a tangible line can be felt in his films, separating the filmmaker from the reality that he is filming. His entire body of work results from patient observation as opposed to constructing a manipulated or staged reality.

Before becoming a filmmaker, Hutton spent a decade living and working on large merchant ships. He paid his way through art school with the money he earned at sea. The experience of witnessing the world by boat undeniably forged the artist’s sense of looking as a means of experiencing time and reality with a more intense focus on the subtleties of vision. The artist explains that, “there’s a kind of culture of survival when you’re out at sea, where you have to develop a kind of visual acuity to know where you are going and what’s happening.” Another defining aspect of Hutton’s work is his early artistic career as a painter. Though the artist abandoned painting for film in the mid-1970s, his films convey a visual connection to the methodologies of painting. As Hutton describes, film is “about painting with the language of cinema.”

Born in Detroit and a current resident of the Hudson River Valley, Hutton’s personal connection to specific places is evident in his work. His long appreciation for the beauty of the Hudson River Valley is expressed in a number of his films including Landscape (for Manon), Study for a River and Three Landscapes. His cinematic treatment of this area has been linked to the mid-19th century painting of the Hudson River School, an American art movement known for romantic depictions of the natural landscape surrounding the Hudson River. Often using his daily life as inspiration, Hutton believes in the adage that truth is stranger than fiction.

Hutton’s oeuvre consists of a rich collection of over twenty films that portray a sense of meditative timelessness. The seamless movement of man and nature appear as continuous forces untouched by time. - www.la-loge.be/project/figures-landscapes-time

In the 1990s and 2000s, when celluloid film was being eclipsed by digital technology, there was an efflorescence of 16-millimeter film installations, with loud projectors and richly colored images, and a revival of interest in deceased pioneers like Paul Sharits and Hollis Frampton. One thing curiously absent — at least in galleries — was work by living artists revealing how they had (or hadn’t) made the switch from film to video.

This show addresses that with three slow, beautiful installations of moving images by James Benning and Peter Hutton. Mr. Benning’s “Tulare Road” (2010) was shot digitally but includes repeating segments, the kind of structural elements determined in the past by looping film stock, but added here in post-production.

Both an extension of, and a follow-up to, works like “The United States of America” (1975), made with Bette Gordon, in which the filmmakers shot through the windshield of a moving car, “Tulare Road” captures a quiet stretch of California highway shot under different conditions: fog, overcast, clear.

Mr. Hutton’s three-channel installations were shot on 16-millimeter film and transferred to video. Deep-hued and expertly composed, the films are also subtle commentaries on labor and globalization.

On Eldridge Street, shipping is the common theme. “At Sea” (2004-07) has footage of a ship being constructed in Korea; images taken from a ship at sea; and film of workers demolishing freighters in Bangladesh, which switches at one point to black and white.

On Orchard Street, Mr. Hutton’s “Three Landscapes” (2013) depicts different forms of industry: salt miners in arid Ethiopia, farmers in the verdant Hudson Valley and repairmen in a familiarly bleak Detroit.

Mr. Benning’s work is formally lean and austerely poetic; Mr. Hutton’s more humanistic, poignant and political. All three exhibit a mastery of the moving picture that is arresting, instructive and impressive.

James Benning and Peter Hutton

NATURE IS A DISCIPLINE

It is difficult to overstate the influence of Peter Hutton and James Benning, two towering figures in American avant-garde cinema and the standard bearers for a deeply attentive approach to landscape. Putting their work side by side in a gallery, as curator Ed Halter has done at Miguel Abreu’s two locations on the Lower East Side, is sure to turn a few heads. Yet while pairing these two lions of experimental cinema may seem faintly gimmicky, Halter convincingly presents them as filmmakers with a similar story. Not only do they share a deep commitment to blurring the lines between natural and industrial landscapes, but both have also moved cautiously in recent years from 16mm to digital formats.

Next door, Hutton’s 2007 film At Sea, a portrait of global cargo shipping, is transformed from three sequential chapters into three adjacent channels. Whereas the theatrical version tells a linear story, the installation emphasizes simultaneity: ship assembly in South Korea, the passage of cargo across the North Atlantic, and shipbreaking on a beach in Bangladesh proceed all at once.

The installation’s multiplying effect, however, is not merely temporal. It also emphasizes At Sea’s iconographic dimensions, breaking the film into photographic tropes that cross-reference a range of related films. The voyage at sea and its colorful containers photographed from the ship’s bridge, for example, invoke Allan Sekula and Noël Burch’s The Forgotten Space (2010). The shipbreaking recalls Michael Glawogger’s strikingly similar scene in Workingman’s Death (2005). And the shipbuilding passage invokes Kelvin Kyung Kun Park’s A Dream of Iron (2014), which was perhaps an explicit homage to Hutton (and Benning and Sekula) to begin with. In the cinema, At Sea emphasizes atmosphere and wonderment, downplaying these intertextual notes. But in three channels, the film becomes ripe for typologizing. We contemplate not just the circulation of cargo, but the circulation of cargo shipping’s cinematic representations as well.

In reference to Benning, Hutton, and others, Scott MacDonald famously wrote that their use of long duration and clinically precise framings seeks to “retrain perception” of space, time, and the environment. Surely, these filmmakers have inspired legions of like-minded artists to slow down and look exhaustively at one thing at a time. So what does it mean to take such a concentrated, deliberative focus and to split it up? Does Nature is a Discipline mark an acquiescence by the filmmakers, a reluctant embrace of digitally-fueled divided attention?

The most convincing argument against such a reading is Hutton’s Three Landscapes (2013). Here,repeating structures and rhyming visual elements draw the viewer into the three screens as a kind of aggregate landscape. Salt mining in Ethiopia is combined with farmworkers in New York’s Hudson Valley and bridge repairmen in Detroit. During much of the 47-minute loop, the landscapes are contrasted—the bridge repairmen are abstracted as faceless, silhouetted lemmings while the salt miners and their camels are depicted in intimate bodily proximity. At other times, however, all three scenes line up perfectly, with workers traversing the horizon in a kind of cosmic unison. The images often repeat and move from screen to screen. Hutton’s orchestration is precise, imaginative, and revealing.

Benning and Hutton often traffic in bits of American iconography that can feel decidedly nostalgic—nondescript roads, agricultural fields, smokestacks—and this show is no exception. This makes it all the more jarring to see their work at Abreu Gallery, where the bookshelves are lined with the “non-philosophy” of François Laruelle and manifestos on “accelerationist aesthetics,” emphatic signifiers of stylish avant-garde leftism. Perhaps this collision was the point all along. If the distracted viewing of the gallery has the effect of speeding up Benning and Hutton’s work, perhaps the accelerationists are also forced to spend more time staring at the surrounding landscape in return. Halter seems to imply that any leftist discourse investigating planetary industrialization or the material traces of global capitalism should include Benning, Hutton, and the tradition of observational landscape cinema. Here, there can be no argument.

The exhibition presents three multi-channel video installations, two by Hutton and one by Benning. The latter’s Tulare Road (2010), the only piece with sound, consists of three similarly framed images of a stretch of highway in California’s Central Valley: in dense fog, in thick cloud cover, and in mostly blue skies. We observe the comings and goings of cars and trucks while looking for subtle differences in the landscape—the quality of the light, but also the patterns of tire tracks on the side of the road or the clarity of the mountains silhouetted along the horizon.

In a compact 18 minutes, Tulare Road demonstrates how a single place can look and feel entirely different. Yet seeing all three images side by side also emphasizes some minor asymmetries in Benning’s framings—the side of the road meets the lower left corner of the frame differently in each take. Presumably, this subtle difference could have been corrected in post-production, but Benning leaves it intact, underscoring his willingness to be imprecise. It’s a reminder that while Benning often sets strict rules for himself, he also feels free to break them.Next door, Hutton’s 2007 film At Sea, a portrait of global cargo shipping, is transformed from three sequential chapters into three adjacent channels. Whereas the theatrical version tells a linear story, the installation emphasizes simultaneity: ship assembly in South Korea, the passage of cargo across the North Atlantic, and shipbreaking on a beach in Bangladesh proceed all at once.

The installation’s multiplying effect, however, is not merely temporal. It also emphasizes At Sea’s iconographic dimensions, breaking the film into photographic tropes that cross-reference a range of related films. The voyage at sea and its colorful containers photographed from the ship’s bridge, for example, invoke Allan Sekula and Noël Burch’s The Forgotten Space (2010). The shipbreaking recalls Michael Glawogger’s strikingly similar scene in Workingman’s Death (2005). And the shipbuilding passage invokes Kelvin Kyung Kun Park’s A Dream of Iron (2014), which was perhaps an explicit homage to Hutton (and Benning and Sekula) to begin with. In the cinema, At Sea emphasizes atmosphere and wonderment, downplaying these intertextual notes. But in three channels, the film becomes ripe for typologizing. We contemplate not just the circulation of cargo, but the circulation of cargo shipping’s cinematic representations as well.

In reference to Benning, Hutton, and others, Scott MacDonald famously wrote that their use of long duration and clinically precise framings seeks to “retrain perception” of space, time, and the environment. Surely, these filmmakers have inspired legions of like-minded artists to slow down and look exhaustively at one thing at a time. So what does it mean to take such a concentrated, deliberative focus and to split it up? Does Nature is a Discipline mark an acquiescence by the filmmakers, a reluctant embrace of digitally-fueled divided attention?

The most convincing argument against such a reading is Hutton’s Three Landscapes (2013). Here,repeating structures and rhyming visual elements draw the viewer into the three screens as a kind of aggregate landscape. Salt mining in Ethiopia is combined with farmworkers in New York’s Hudson Valley and bridge repairmen in Detroit. During much of the 47-minute loop, the landscapes are contrasted—the bridge repairmen are abstracted as faceless, silhouetted lemmings while the salt miners and their camels are depicted in intimate bodily proximity. At other times, however, all three scenes line up perfectly, with workers traversing the horizon in a kind of cosmic unison. The images often repeat and move from screen to screen. Hutton’s orchestration is precise, imaginative, and revealing.

Benning and Hutton often traffic in bits of American iconography that can feel decidedly nostalgic—nondescript roads, agricultural fields, smokestacks—and this show is no exception. This makes it all the more jarring to see their work at Abreu Gallery, where the bookshelves are lined with the “non-philosophy” of François Laruelle and manifestos on “accelerationist aesthetics,” emphatic signifiers of stylish avant-garde leftism. Perhaps this collision was the point all along. If the distracted viewing of the gallery has the effect of speeding up Benning and Hutton’s work, perhaps the accelerationists are also forced to spend more time staring at the surrounding landscape in return. Halter seems to imply that any leftist discourse investigating planetary industrialization or the material traces of global capitalism should include Benning, Hutton, and the tradition of observational landscape cinema. Here, there can be no argument.

Peter Hutton received his BFA and MFA from the San Francisco Art Institute. Hutton has taught at CalArts, Hampshire College and Harvard University. He currently teaches at Bard College. In 2008, his work was the subject of a retrospective at MoMA. His films have been featured in a number of international film festivals including New York, Vienna, Rotterdam, London and Toronto. His work has also been exhibited at the Whitney Biennial (1985, 1991, 1995, 2004), George Eastman House, Museum of Contemporary Art Oslo, among others. He is the recipient of a Guggenheim Fellowship and has received grants from the National Endowment for the Arts, DAAD/Berliner Künstlerprogramm, Rockefeller Foundation, etc. His work can be found in the collection of many museums including MoMA, Centre Pompidou and the Austrian Film Museum.